ENDURING TEMPORARINESS

To complete something suggests to strive for perfection. It is also a merely time-based idea, in other words it concerns all that happened before we disengaged from the linearity of history and the idea that events might pass or occurrences disappear.

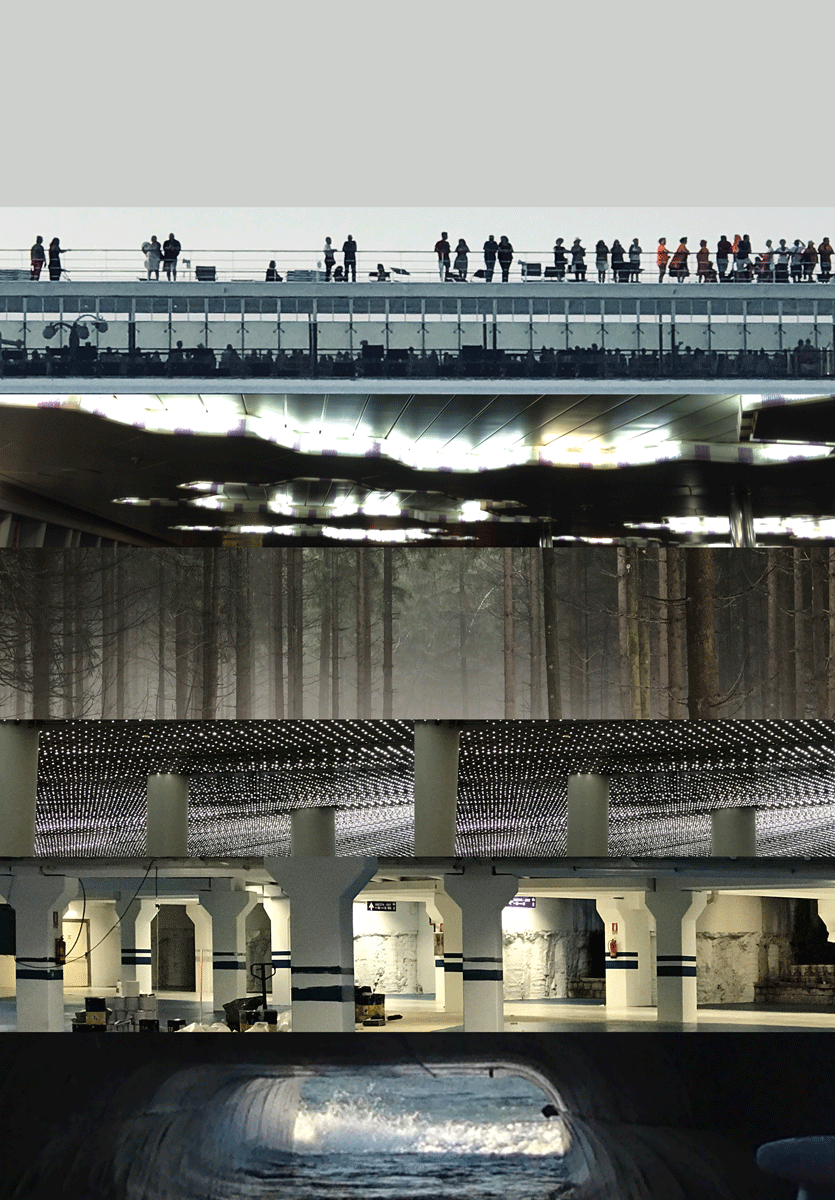

The New Domestic Landscape, digital C-print, 2021

The New Domestic Landscape, digital C-print, 2021TWILIGHT

Imagine yourself in the twilight. Instances of flux, entropy, uncertainty, imminence, virtuality, urgency. Momentary concerns. The implausible phenomena incessantly reformulating around us are not easy to recount. The proof must be precise or it risks to haunt you as a fabrication. One way is to take a distance from the story and remain with the factual. Another one would be to synthesize the truth into fiction by amplifying exactly that distance to elaborate the story. Then there are those phenomena that hover in our minds, seemingly idle, low-res and out of focus. Recurring sojourns in Waiting Land had made the plot superfluous. Because in a near future of hyper densities, proliferations, and the production of redundancies, architecture would change from being a container—a repository of accumulated wealth, belongings, choices, and preferences— into a momentary absence, a void, receptive and reactive to all kinds of agencies. A threshold.|1 The following is a recollection of recent events, with no forecast. The rush for proof—or truth—has lost its appeal. Our senses tune into the distant broadcasts of planes and stratifications we will not conquer nor visit or study. Just view. Maybe follow.

“In a few hundred thousand years, extraterrestrial forms of intelligence may incredulously sift through our wireless communications. But imagine the perplexity of those creatures when they actually look at the material. Because a huge percentage of the pictures inadvertently sent off into deep space is actually spam.” |2

—Hito Steyerl

—Hito Steyerl

DEVELOPING STORIES

To understand the times ‘they’ lived in we tend to revisit Modernism and the Metabolist, Brutalist, Structuralist, Rational, and Radical movements that formed alongside. Then we understand that there are multiple formulations, that you and I may live in different ones, not necessarily in different times but in various ecologies, environments and truths.

In 2008, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster shows TH.2058, the interiors of Tate Modern 50 years into the future of a London afflicted by perpetual rain. Now Tate Modern provides shelter for people, a storage space for few strangely outgrown art works, some books, and other remains of culture regarded collectively. |3

In 2011, in Some Experiments in Art and Politics, Bruno Latour points out the need for a new vocabulary of politics, referring to Isabelle Stengers’ suggestion of ‘cosmopolitics’ which “will come precisely from a new attention to other species and other types of agencies.”|4 Latour expands that “here again, art, philosophy, ecology, activism, and politics exchange their repertoire on order to redefine the actors, the claims, the forums, and the emotions of political involvement.”|5

In 2012, the House of World Cultures Berlin announces the Anthropocene Project with the calling to epitomize our recollections, to acquaint us with the sound, atmosphere, haptics, nutrients, pandemics and movements of the planetary era we now live in, and to observe how we may partake and live on from here.|6 The same year, Cyprien Gaillard performs What It Does To Your City, a live audio performance and ballet of caterpillars on a private investor’s construction site in central Berlin, provoking all possible questions.|7

Architettura Reversibile, digital C-print, 2021

Architettura Reversibile, digital C-print, 2021Three Taipei Biennals: in 2014, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud, The Great Acceleration seeks to “to renegotiate our relationship with both technosphere and biosphere.” |8 In 2018, curated by Francesco Manacorda and Mali Wu, Post-Nature—A Museum as an Ecosystem positions the Biennale itself as a living organism that faces the severe environmental problems of industrialization, urbanization and global economic pressure on a planet “of interdependent ecosystems, populated by diverse and mutually reliant beings.” |9 The most recent one in 2020, curated by Bruno Latour, Martin Guinard, and Eva Lin, presents You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet, summarizing in its title the problems encountered by the whole Earth, and suggesting that if originally “geopolitics implied there were different people with different interests fighting for territories that were parts of the same nature, today it is the composition of this very nature that is at stake.” |10

In 2017, Pierre Huyghe assembles Exomind (Deep Water) in the gardens of the Dazaifu Tenmangu Shrine, Fukuoka Prefecture. Left to their own life cycles, this set of works from the past decade adds all kinds of living creatures to the landscape—insects, plants, animals, and human beings—in order to explore their behavior and interactions, epitomizing the implausible phenomena of the twilight we live in. |11 That same year, Lara Favaretto shows her ongoing work Digging Up. Atlas of the Blank Histories at Villa Arianna in Castellamare di Stabia, near Pompeii. Translating Chris Marker’s time travel attempts in his iconic film La Jetée, she employs core boring to extract sub soil samples from archeological sites. Unveiling an intrinsic entanglement of times and spaces, she brings to light “a spectrum filled with potential, discovery, and extraordinary tales. ...The cores constitute the DNA of the places they come from and sampling them makes it possible to ensure reproducibility in the future, thus reversing the past into a sort of memory of what is to come, impressed upon the material extracted from the bowels of the Earth.” |12

In 2021, Prada and AMO screen the Fall Winter 2021 menswear collection Possible Feelings as an in-/exterior “simultaneously both or neither” and abstracted to a “a panoply of surface, texture and textile.” Facing this suggestive freedom of interpretation and expression, we tune in with our needs for intimacy, contact, exchange or other forms of relating. Something, until recently, unheard of. |13 In their incompletion and imperfection, all of these works are laboratories for implausible phenomena, the precarious divergence between fiction and reality. And it goes on. What the 20th century meant to shaping the built environment, the beginnings of the 21st century scrutinized as to why and where things went off course. Conversations have since turned to societies, cultures, survival, urgencies uncovering a gaping hole of destruction and with it—if we allow it to happen—the allure of a synthetic wilderness, of uncertainty, and chance.

EXTENDED EXISTENCES

When studying civilization we used to review evidence: photographs, visualizations, maps, diagrams, texts and other interpretations of human manifestations. Fascinated, we also knew all was different since these images first appeared, that meanings and memories are ever evolving interpretations. We looked ‘back in history’ to understand the present— clearly uncomfortable with the idea of contemplating alternative existences. We also believed to design for the future, but really, all was there at once. History is about the past, the categorization of actions and events over time. History helps us to keep order, some use it to explain..., yet it continuously fails us in predicting what comes next. History is about the notorious organization into classifications and has but created disagreements, protests, destruction and all kinds of migration.

Narrative is about tales, versions, sketches and stubs, revelations and renderings. A narrative is also an interpretation and encourages our personal involvement with all there is, at any time. To understand the demeanor of the collective that we take as our world, we must allow for other species and new genres, edit what we thought we knew, and challenge relevance. Because “...in this extended, mobile present, the future may already have taken place and the past may still be taking shape.” |14

Salone del Mobile, digital C-print, 2021

Salone del Mobile, digital C-print, 2021NOTES

1| “Threshold” here refers to an earlier text, published in the monograph ‘Waiting

Land’ (Berlin, 2017) by the same authors. The following quote provides the wider context of ‘Enduring Temporariness.’

“CROSSOVER: Waiting Land shows a landscape at the margins—off course from the clearly outlined, indivisible, controlled and productive image. Its apparent undecidedness and non- functionality questions any raison d’être and seemingly deprives landscape of definition and use. It is really about de-registration or disappearance from our awareness. It’s a back and forth between evidence and interpretation, in ongoing rearrangement and re-formation. It is as much about what we register as about what there is. And in our updated modes of seeing (or screening) we step into a mediated reality which consists of a composite view (or experience), the result of augmenting or diminishing modifications. This is the crossover into the stub. Now it’s about location and condition at the same time: as location Waiting Land occupies a territory deprived of human activity, as condition it renders an environment as the effect of human activity.”

2| Hito Steyerl, ‘The Spam of the Earth: Withdrawal from Representation,’ in: ‘The Wretched of the Screen,’ Sternberg Press, 2012

3| Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, ‘TH.2058’ (2008/09), Tate Modern, London

4| Isabelle Stengers, ‘Cosmopolitics I,’ trans. Robert Bononno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). Quoted in: Bruno Latour, ‘Some Experiments in Art and Politics,’ e-flux Journal #23, 2011

5| Bruno Latour, ‘Some Experiments in Art and Politics,’ e-flux Journal #23, 2011.

www.e-flux.com/journal/23/67790/some-experiments-in-art-and-politics/.

6| Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin.

www.hkw.de/en/programm/projekte/2014/anthropozaen/anthropozaen_2013_2014.php.

7| Cyprien Galliard, ‘What It Does To Your City’ (2012), Schinkel Pavillon Berlin

8| Taipei Biennale 2014, www.taipeibiennial.org/2014/en/index.html.

9| Taipei Biennale 2018, www.taipeibiennial.org/2018/?lang=en.

10| Taipei Biennale 2020, www.taipeibiennial.org/2020/en-US/Home/Index/0.

11| “Shown for the first time in 2012 in Kabul, on the occasion of dOCUMENTA 13, the project was expanded and was shown again in Cappadocia in 2017. For this new chapter of the Atlas of the Blank Histories, the investigation started out from a series of stories set in Pompeii, both inside and outside the archaeological area, reaching all the way to Vesuvius, in Castellammare di Stabia, Herculaneum, Torre del Greco, and as far as Pozzuoli. ...A plaque with the extraction data will be set up at each point where a core sample has been taken, creating an open-air museum of the local area, starting from the Archaeological Park of Pompeii all the way to the slopes of Vesuvius.” www.madrenapoli.it/sala-media/25-ottobre-2018-lara-favaretto-digging-up-atlas-of-the-blank- histories/.

12| Pierre Huyghe’s ‘Exomind (Deep Water)’ (2018 ongoing), actively complements the shrine’s gardens with a concrete cast as the reference point for a wax hive, bee colony, orange tree (Daidai), plum tree (Tobiume descendant), plants, sand, stones, calico cat, ants, spider, butterfly, axolotl and insects. The various components, living or not, gather around a concrete pond with waterlilies (Giverny descendant)—a present-day transplant from Claude Monet’s original garden pond famously depicted in his ‘Nymphéas’ series.

13| ‘Possible Feelings,’ Prada menswear collection F/W 2021/22.

www.prada.com/ww/en/pradasphere/fashion-shows/2021/fw-menswear.html.

14| Lara Favaretto, ‘Digging Up. Atlas of the Blank Histories’ (2012 ongoing). www.madrenapoli.it/sala-media/25-ottobre-2018-lara-favaretto-digging-up-atlas-of-the-blank- histories/.